by Kate Redmond

Burrowing Wolf Spider

Greetings, BugFans,

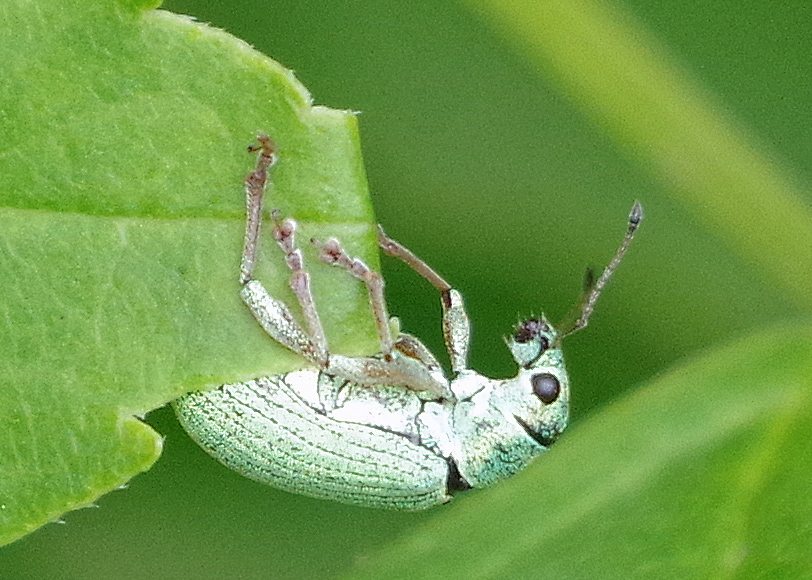

One afternoon in late June as the BugLady was walking along the cordwalk at Kohler-Andrae State Park, she noticed a few half-inch-ish holes in the sand, holes that had more “structure” than the ones she makes with her walking stick, and larger than those made by solitary wasps. She took a couple of throwaway shots and was very surprised when she put one up on the monitor and noticed eyes and legs! She photographed more holes on subsequent trips, but their openings were unoccupied. The cordwalk goes over both dunes with loose sand, and areas with low vegetation and a somewhat more organic soil. The holes were in the loose sand.

She asked BugFan Mike if it might be a wolf spider called the Burrowing Wolf Spider (Geolycosa missouriensis). He said that was a possibility and urged her (as always) to be conservative in her spider IDs, especially considering the quality of the picture. Amen, Mike!

Wolf spiders (family Lycosidae) (lycosa is Greek for “wolf”) are common, hairy, nocturnal, ground-dwelling hunters with very good eyesight. Most species of wolf spider do not spin trap webs.

[Quick Detour: nowadays, we use the name “tarantula” to refer to a group of non-Lycosid, palm-sized, hairy, tropical spiders https://bugguide.net/node/view/289856/bgimage. The BugLady’s 4th grade teacher told a story of being in basic training in California and digging foxholes that bisected tarantula borrows, which she thought was pretty cool (she doesn’t remember much else of 4th grade). Anyway, the original tarantula is a southern European/Italian wolf spider. Legend had it that if one bites you, you‘re doomed to dance a dance called the tarantella. The BugLady assumes that when they saw the big hairy spiders, those settlers from the Old Country applied the name of a scary spider that they already knew about. And in fact, a number of other groups of large spiders have been called tarantulas, too].

Wolf spiders in the genus Geolycosa are called the Burrowing wolf spiders (geo means “earth”). They live in vertical burrows, and they are habitat specialists, preferring loose, sandy soil that makes digging easier. Of the 75 species in the genus worldwide, 18 live in North America north of the Rio Grande. They have strong legs and (short spider anatomy review, here) two strong chelicerae (jaws) that are used as pincers and that are tipped with fangs. A pair of palps, which look like a short leg on each side of the chelicerae, are used to manipulate food https://keys.lucidcentral.org/keys/mites/ismite/html/a10h_Mouthparts.html.

Burrowing wolf spiders are generally Stay-at-Homes – the spiderlings don’t scatter far from the maternal burrow. They initiate their own lair when they’re very small, enlarging it as they grow, rarely straying more than an inch or so away from it, and retreating into it when alarmed. Populations remain fairly restricted.

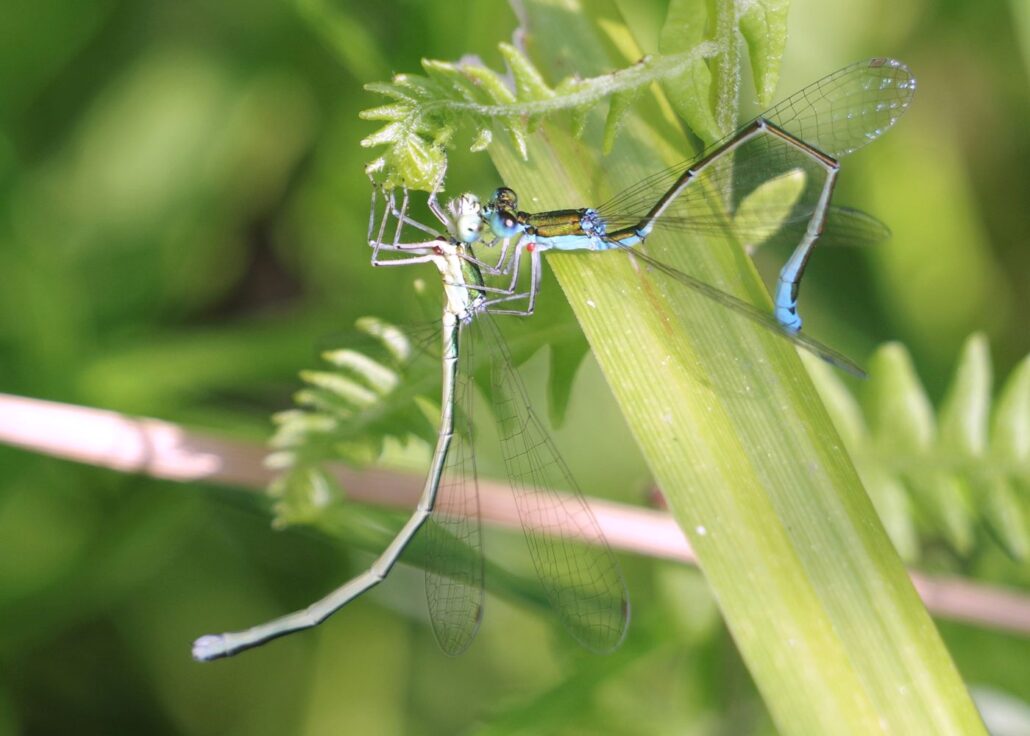

They are tied to one spot, with fixed pools of prey and of potential mates, but the trade-off is an absence of Flying Monkeys. They can dodge predators and avoid desiccation within a relatively stable, climate-controlled tunnel. In early fall, though, when a young spider’s fancy turn to love, he abandons that security and sets off in search of romance. They mate in late summer, but the gravid female doesn’t make an egg sac until the next spring. She displays maternal care – carrying around first her egg sac, and later her young https://bugguide.net/node/view/114423/bgimage (and not eating them). Spiderlings hatch in early summer, overwinter as immature spiders in their first year, and become adults in late summer of their second year.

Gratuitous vocabulary word(s) of the day: some Geolycosa species are “turricolous” (they live in areas that have some leaf litter, and they create little turrets or lips made of debris, sand, and silk around the opening of the tunnel https://bugguide.net/node/view/912651/bgimage), and others are “aturricolous” (they don’t).

Bracing itself within the tunnel with its legs, the spider uses its fangs to loosen the sand, and if the sand is not moist enough on its own, it uses silk to compact the sand into a pellet. It uses its chelicerae and palps to move the pellet to the opening of the burrow, and it disposes of the pellet by flicking it away (sometimes a foot away) with its forelegs – unless it’s going to use it to build a turret. Burrowing wolf spiders reinforce the upper section of their lair by covering the walls with a few layers of silk. Summer burrows are less than a foot long, but winter burrows may be more than five feet deep. Researchers who studied Geolycosa missouriensis noted that a spider excavating an average burrow removed 918 sand pellets.

Larry Weber, in Spiders of the North Woods, says that if you stick a grass stem down an occupied Geolycosa missouriensis burrow, the spider will grab it and hang on, and you can dig out the entrance and see the spider. Seriously, Larry? All that work – 918 pellets – why would you?

They ambush their prey – lurking in the entryway and darting out to grab nocturnal invertebrates like crickets as they wander by. They feed within, and the indigestible bits of prey fall to the end of the tunnel. About the Geolycosa, the publication “The Insects and Arachnids of Canada, Part 17,” notes that when kept in captivity, “They should be individually caged because they are fierce predators, and cannibalism can soon reduce the culture to a single well-fed individual.”

So – who was in that burrow? Here are a few possibilities.

A BURROWING WOLF SPIDER (Geolycosa missouriensis), aka the Missouri Earth Spider or the Missouri Wolf Spider, is found on sandy loam soils from Texas to Ontario and Saskatchewan https://bugguide.net/node/view/862935/bgimage. Its leg-spread is around 1 ½”.

The gravid female uses sand and silk to fashion a door for the tunnel in winter. She will bring her egg case into the sun at the burrow opening on warm, spring days, and females can be found in their burrows carrying young on their back in early summer. Sources are ambivalent about whether Geolycosa missouriensis makes turrets.

GEOLYCOSA WRIGHTII (no common name) https://bugguide.net/node/view/1285635/bgimage. It’s not as common, and its range is restricted to sand dunes and beaches from Indiana and Illinois north through the Western Great Lakes states and provinces. Females protect their newly-hatched offspring by sealing themselves into the tunnel with their young for a few days, until they find their feet. Geolycosa wrightii doesn’t make a turret.

The BEACH WOLF SPIDER (Arctosa littoralis https://bugguide.net/node/view/771440/bgimage) also makes silk-lined tunnels, but unlike the Geolycosa, it hunts at night by chasing after prey on beaches and wetland banks, and shelters in tunnels or under driftwood in the day. Entomologist Eric Eaton says that if you’re abroad on the beach at night, wearing a headlamp, “When the beam of the light hits a wolf spider, the animal’s eyes will glint a blueish-green shine…..and a female with young on her back looks like a diamond-studded stone.”

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/