by Kate Redmond

Bugs without Bios XIX

Howdy, BugFans,

Bugs without bios – those humble (but worthy) bugs about whom little information is readily available. Today’s bugs check those boxes as species, but they have something in common – their lifestyles are similar to those of close relatives who have already starred in their own BOTW.

The BugLady found this PREDACEOUS DIVING BEETLE (Hydacticus aruspex) (probably) in shallow water that was so plant-choked that the beetle had trouble submerging. Diving beetles are competent swimmers, tucking their two front pairs of legs close to their body and stroking with powerful back legs. When they submerge, they carry a film of air with them to breathe, stored under the hard, outer wing covers (elytra). They can fly, too, though they mostly take to the air at night.

As both larvae and adults, Predaceous diving beetles are aquatic and carnivorous, dining on fellow aquatic invertebrates. Larvae (called water tigers) grab their meals with curved mouthparts and inject digestive juices that soften the innards, making them easy to sip out (generic water tiger – https://bugguide.net/node/view/49848/bgimage). They eat lots of mosquito larvae. Adults grab their prey and tear pieces off. Not for the faint of heart.

Hydacticus aruspex (no common name) is one of five genus members in North America and is found across the continent. It comes in both a striped and a non-striped form https://bugguide.net/node/view/296320/bgimage. It overwinters as an adult, under the ice, and romance blossoms in spring. For more information about Predaceous diving beetles, see https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/predaceous-diving-beetle-revisited/.

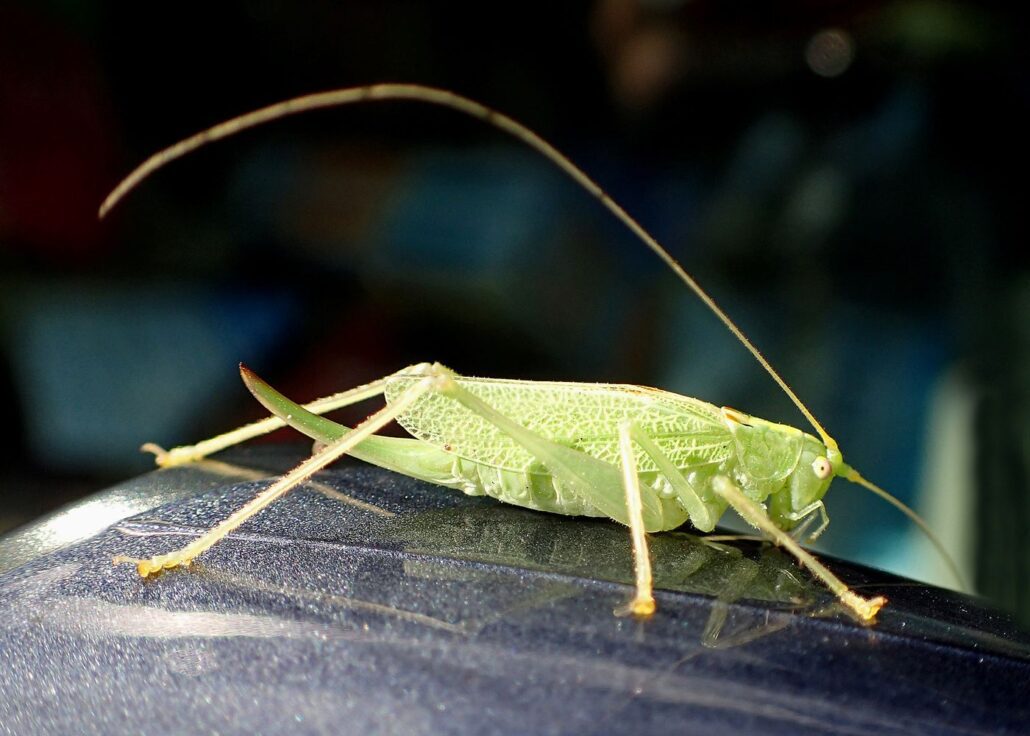

These spectacular OBLIQUE-WINGED KATYDIDS (probably) were climbing around on Arrow Arum in a wetland that the BugLady frequents. Katydids are famous singers whose ventriloquistic calls may be heard day and night (though older ears may strain to hear them – test your hearing here https://www.listeningtoinsects.com/oblong-winged-katydid). They “sing” via “stridulation” – friction – in their case, by rubbing the rigid edge of one forewing against a comb-like “file” on the other (the soft, second set of wings is only for flying, and they do that well). They hear with slit-like tympana on their front legs. Most Katydids are vegetarians, but a few species are predaceous.

Oblong-winged Katydids (Amblycorypha oblongifolia) are “False katydids” (here’s a True katydid https://bugguide.net/node/view/2207342/bgimage) in the Round-headed katydid genus. They are found in woods, shrubs, and edges throughout the eastern US, often in “damp-lands,” often on brambles, roses, and goldenrods. The dark, mottled triangle on the top of the male’s thorax is called the “stridulatory field” – a rough area that is rubbed to produce sound. Oblong-winged katydids have a large stridulatory field.

Katydids, both in color and in texture, are remarkably camouflaged – except when they’re not. Here’s an awesome color wheel of katydids https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/amblycorypha_oblongifolia.htm.

For more information about the large katydids (including the origin of their name), see https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/katydid-rerun/.

The BugLady came across this cute little MOTH FLY (Clytocerus americanus) (probably) on a day that she couldn’t take an in-focus shot on a bet! Fortunately, bugguide.net contributors did better https://bugguide.net/node/view/426325/bgimage, https://bugguide.net/node/view/695589/bgimage. Despite their name, Moth flies are moths, not flies or weird hybrids. They are tiny (maybe 1/8”) and hairy, and are weak fliers, and until she saw this one, the only Moth flies she had ever seen were indoors, in the bathroom (where they earn another of their names – “drain flies”). Species that live outside are, like this one was, often found near wetlands.

There are only one or two species in the genus Clytocerus in North America, and they have strongly-patterned wings and very hairy antennae. Not much is known about their habits. According to Wikipedia, adult Clytocerus americanus feed on “fungal mycelia and various organisms which inhabit wet to moist environments. Larvae are assumed to be detritivores.”

Find out more about moth flies here https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/moth-fly/.

MASON WASP – This is what happens when the BugLady buys garden stakes! After various small, solitary wasps populate the empty interiors with eggs, the BugLady can’t possibly stick them into the ground!

As their name suggests, female Mason wasps use mud to construct chambers in preexisting holes to house both their eggs and the cache of small invertebrates that their their eventual larvae will eat.

The Canadian Mason Wasp (Symmorphus canadensis) suspends an egg from the chamber roof or wall by a thread and then adds 20 or more moth or leaf mining beetle larvae before partitioning it off with a wall of mud and working on the next cell https://bugguide.net/node/view/509856/bgimage. She leaves a “vestibule” at the end of the tunnel/plant stake between the final chamber and the door plug.

Heather Holm, in her sensational Wasps: Their Biology, Diversity, and Role and Beneficial Insects and Pollinators of Native Plants, discusses the hunting strategy of genus members: “Symmorphus wasps hunt leaf beetle larvae (Chrysomela); these beetles have glands in their abdominal segments and thorax that emit pungent defensive compounds. These compounds are derived from the plants that the larvae consume. ….. In addition to using visual cues to find their prey, it is likely that Symmorphus wasps use olfactory means to find the beetle larvae. Symmorphus males have been observed lunging at Chrysomela larvae, mistaking the larvae for adult females [female mason wasps] that, after capturing and handling prey, smell of the offensive compounds.

Here are two previous BOTWs about mason wasps, each a different genus than the Canadian Mason wasp: https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/bramble-mason-wasp/ and https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/four-toothed-mason-wasp/.

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/