by Kate Redmond

Bug o’the Week Parnassia Miner Bee a Bee and its Flower

Howdy, BugFans,

A while back, BugFan Matt asked the BugLady if she had ever photographed a small bee on a Grass-of-Parnassus flower. Grass-of-Parnassus (not really a grass) is one of her favorite flowers (despite the fact that it shouts “Fall is coming!” every time she sees it). She photographs it a lot in the closing days of August, and it turned out that she had seen the bee, but she hadn’t realized how special it was.

As BugFans will recall from those six weeks of mythology in high school English, Mount Parnassus was sacred to Apollo and was home to the Muses in Greek mythology. Allegedly, cattle on Mount Parnassus grazed on the plant, and so it was promoted to honorary grass status.

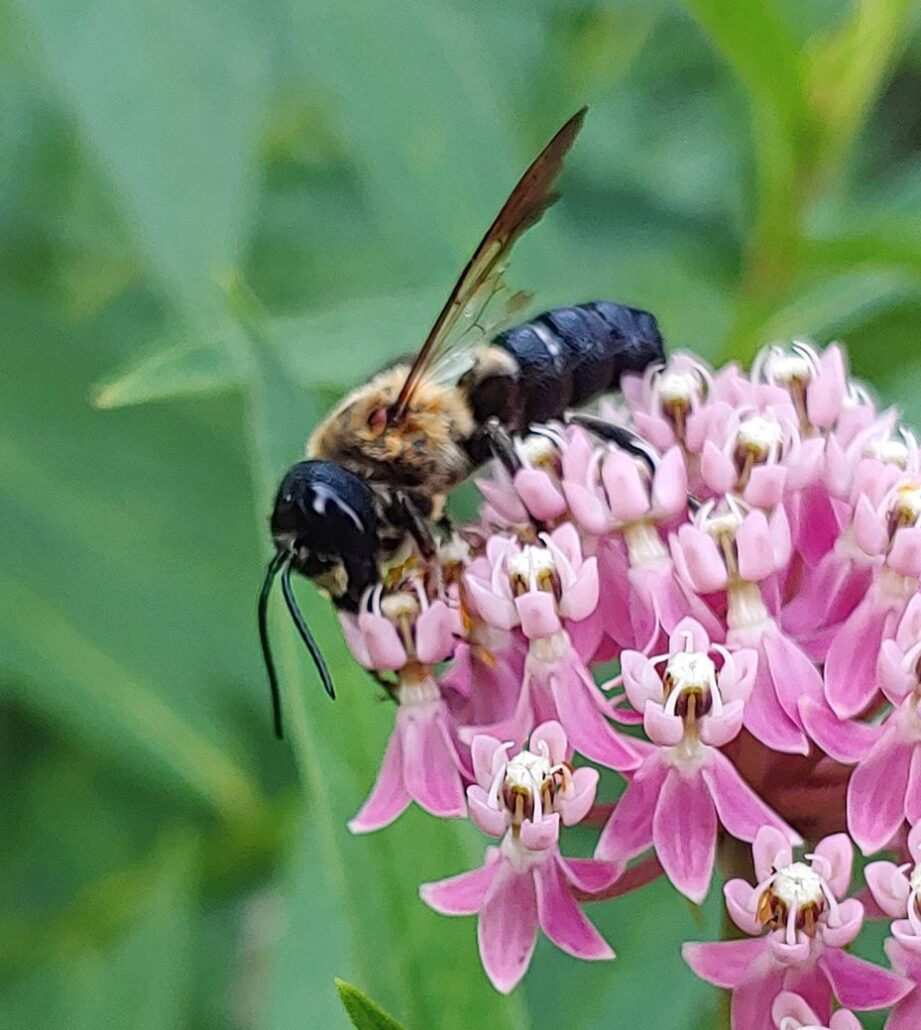

Mining bees have been featured on these pages before (https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/red-tailed-mining-bee/). They are small and fuzzy and are among our earliest pollinators (the fuzz keeps them warm on chilly spring mornings). Some are catholic in their tastes (polylectic), but many species are linked to a single, small group of related plants (oligolectic), and some zero in on only a single species (monolectic). Many have no common name at all, but like the Parnassus miner bee, their scientific name may include a nod to their affiliated plant.

They emerge when their host plants emerge, make tunnels a few inches deep in the ground, scoop out, waterproof, and provision chambers within them with pollen and nectar, and then install the next generation, which will overwinter underground and repeat the cycle when their flower reappears. The various species of mining bees and their flowers span the growing season, and late summer mining bee species are most often seen on goldenrod and on members of the carrot family.

Except the PARNASSIA MINER BEES (Andrena parnassiae), which are found only where Grass-of-Parnassus lives – calcareous fens (another name for the plant is the Fen Grass-of-Parnassus) and other wet, alkaline meadows and wetlands. They’ve been recorded in Wisconsin, Michigan, Vermont, and North Carolina. A journal article from the early 20th century said that the bee’s flight period went from August 25 to September 26, and that its only known Wisconsin occurrence was on the Lake Michigan bluffs in the Milwaukee suburb of Whitefish Bay, on a plant that was misidentified, due to an error in an early botany reference, as Carolina Grass of Parnassus (which is found in Florida and the Carolinas).

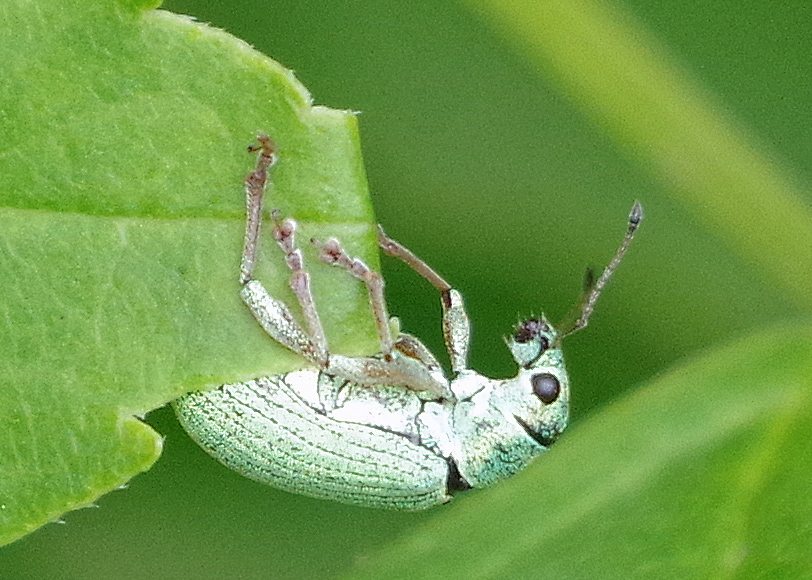

The hairs on their body act as pollen collectors, too, and they have pollen baskets on their back legs. Parnassia Miner Bees only glean pollen from Grass-of-Parnassus flowers (and they are important pollinators of it – more about that in a sec), but the flowers are also visited by other bee species, syrphid and other small flies, ichneumon wasps, butterflies, (and the BugLady found a lightning beetle checking it), and by spiders with a taste for pollinators.

When you (or a bee) look at the flower, what do you see? The green lines on the five petals are nectar guides, beckoning the bee to follow them to the nectar source. But the bee also notices a ring of 15 filaments at the base of the petals (actually five sterile stamens or staminoides, each divided into three prongs), each topped with what looks like a drop of nectar, resembling the (male) stamens of the flower. These are false nectaries that provide no nectar reward but serve to get the bee into the right vicinity – the real nectar lies at the base of the filaments.

There are also five true stamens, each topped with a pollen-producing anther, and in the green center of the flower, the female flower parts – stigma, style and ovary (collectively called the pistil).

[Nota Bene: the BugLady learned just enough Botany in college to make it through the Botany final, and she’s been forgetting it ever since, so she has to pull up a chart on Wikipedia every time she tries to write about flowers.]

The BugLady was wondering about the pedigree of Grass-of-Parnassus and she encountered some confusion about that. Several reputable sites reported that it was in the Saxifrage family, but another said that there was only a very distant familial connection. Others put it in the Staff tree family Celestraceae, and still others placed it in its own family Parnassiaceae (though it may be destined to rejoin the Celestraceae).

Putting it all together: It’s a sweet little flower that has worked out some complex strategies to spread pollen and to avoid self-fertilization. Consider the five true stamens. Rather than maturing all at once, only one lengthens, matures and produces pollen per day, arcing over the top of the pistil. After the first day, its anther turns brown and the filament relaxes against the ring of petals, and another stamen grows and produces pollen.

The pistil does not grow or become receptive to incoming pollen until after all five stamens have matured, making it impossible for the flower to self-pollinate. Eastman, in The Book of Swamp and Bog, says that the flowers exhibit protandry – that is, the flower, which has both male and female parts, is unisexually sequenced, the male parts completing their development before the female parts start. To put it another way, the flowers have a male phase and then a female phase.

When a bee is tempted by the beads of false nectar and orients itself to harvest some, it straddles an anther, and pollen is picked up by the hairs on its abdomen. When it visits the next flower, pollen is brushed off, hopefully onto a flower whose female parts are ready to receive it (“xenogamy” “stranger marriage” — a flower breeding not with itself but with another).

Bryan Pfeiffer, naturalist and blogger (“Chasing Nature”) and Grass-of-Parnassus watcher, has written some very nice entries about his experiences with both the flower and the bee – here are two – https://bryanpfeiffer.com/2021/09/06/being-with-flowers/ and https://chasingnature.substack.com/p/a-duplicitous-flower-and-its-rare#:~:text=Parnassia%20Miner%20gets%20that%20pollen,butterfly%20caterpillars%20eating%20only%20milkweeds (this one has a nice shot of a bee on the stamens).

Xenogamy, polylectic, oligolectic, monolectic, staminoides, protandry, stamens and pistils and anthers, oh my – it’s January, time to dust off our brains. There will be a quiz.

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

As a bit of lagniappe, here’s a lovely video about butterflies (audio on): https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/ten-fun-facts-about-butterflies/?utm_source=smithsoniandaily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=editorial&spMailingID=49251228&spUserID=ODg4Mzc3MzY0MTUyS0&spJobID=2620068856&spReportId=MjYyMDA2ODg1NgS2

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/