by Kate Redmond

The Monarch Butterfly Problem

Howdy, BugFans,

The BugLady wrote this for an upcoming newsletter of the Lake Michigan Bird Observatory (an organization that would love your support). It started out as a simple report about this year’s survey of overwintering Monarch Butterflies, but then it took the bit in its teeth and became oh-so-much more. Put your feet up.

Every fall, most of the Monarch Butterflies east of the Rockies set their compass for a small patch of mountains just northwest of Mexico City. This winter’s count of eastern Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus plexippus) overwintering in the oyamel fir forests of central Mexico was the second lowest since annual censusing began in 1993. In the 1990’s, the eastern Monarch Butterfly population was estimated at 70 million, and today’s numbers represent an 80% decline in population.

The census is not an actual nose-count of the butterflies themselves but is a measurement of the area they occupy. They’re densely concentrated on their wintering grounds — scientists estimate between 20 and 30 million Monarchs per hectare (about 2.5 acres). The lowest area, 0.67 hectares (1 66 acres), occurred 10 years ago, and the largest ever, in 1996-97, found 45 acres occupied. This year, Monarchs were seen on 0.9 hectares (2.2 acres), down 59% from the 2022-2023 season (Dr. Karen Oberhauser, founder and director of the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project (https://mlmp.org/), points out that 2.2 acres is smaller than two football fields). It’s felt that almost 15 acres of overwintering butterflies are needed to maintain a healthy eastern population. “Monarch populations [are] at a level that most scientists suggest is not sustainable,” says Dr. Oberhauser. Western Monarchs, residents and migrants along the Pacific Coast, are treated as a separate population.

Migration is expensive, energy-wise, and is dangerous, and the list of hazards is long. Land use changes and habitat loss, herbicides and pesticides, loss of milkweed, car-butterfly collisions, climate change that brings harsh winter conditions to central Mexico or storms as the butterflies prepare to depart, or that puts migrating butterflies out of sync with nectar plants on their spring migration, high temperatures that reduce the nutritional value of milkweed plants, and severe drought along the fall migration route through “the Texas Funnel” have all been suggested as factors.

The integrity of the fir forests themselves is critical, but the illegal logging that has reduced the forest size and cover in the past was held to a minimum last year. The butterflies depend on a dense forest to act as insulation so they don’t have to expend as much energy staying warm, dry, and hydrated.

Quick review of Monarch biology and migration — there are four or five generations annually, and the last brood of the year is extraordinarily long-lived for a butterfly. It emerges in August or September, and while the earlier generations are reproductively active, this final generation is not. Signaled by decreasing day length, lowering angle of the sun, cool nights, and increasingly leathery milkweed leaves, their reproductive organs don’t mature. Instead, they apply their energy to a journey – a leisurely trip that can cover more than two thousand miles and take two months. The butterflies feed on nectar from a wide variety of flowers as they wend their way south, and while a newly-emerged Monarch in Wisconsin has about 20 mg of fat in its body, a Monarch newly-arrived in the oyamel fir forests of Mexico may carry 125 mg of fat. They eat little on their wintering grounds.

With the warming temperatures of late March, they become reproductively ready and head north through northern Mexico and our Southern states, laying eggs as they go, careful not to get ahead of the emerging milkweed plants. Their young — the first-generation offspring of the Mexican butterflies — keep moving and recolonize the north, often arriving in Wisconsin in mid-May and in Canada shortly after that (Southern summers are too hot for the caterpillars to thrive).

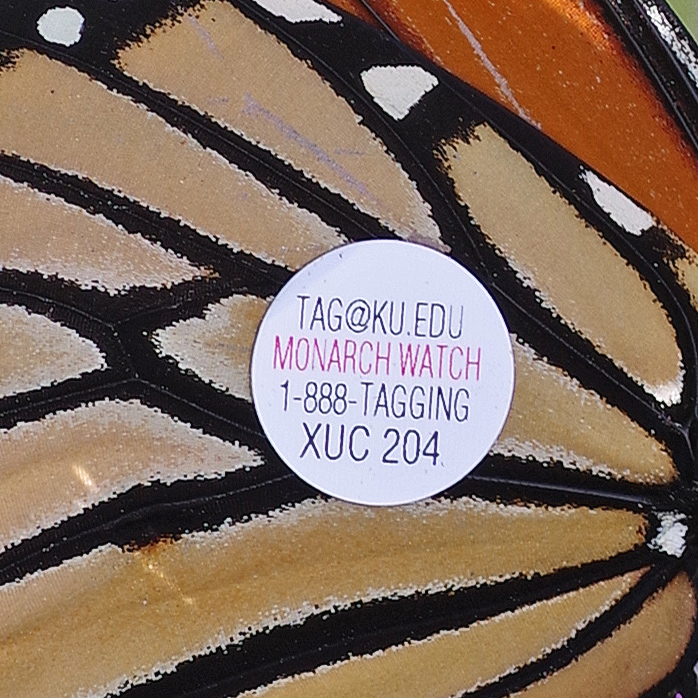

Their offspring – the second generation out of Mexico, continue to lay eggs and may fly a little farther north, but most have reached their destinations by the end of June. The “job” of this short-lived generation (and of the next generation, if there’s time for one) is to stay put and use their energy to build up the population. The migratory final generation, sometimes called Gen 5 or the Super Generation, is the only one that is tagged.

This complicated dance depends on good weather, milkweeds for caterpillars, and abundant nectar plants for adults. Monarchs will lay their eggs on a variety of milkweed species, but Common milkweed is the favorite.

Follow the northward wave of Monarchs here https://maps.journeynorth.org/

There have been passionate efforts in past years to list the Monarch as an Endangered Species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Classification under the ESA is a lengthy process, there are many other deserving candidates, and listing requires both a recovery plan and a dedicated budget https://uwm.edu/field-station/

Monarch populations are subject to wide swings, but a low year followed by another low year lessens the possibility of a speedy comeback. Overall population levels in the summer of 2023 were not alarming, but severe heat and drought in the Texas Funnel migratory corridor probably resulted in fewer Monarchs finishing their journey to Mexico.

Based on a few recent studies, there are voices, even voices within the Monarch Butterfly community, that suggest (counterintuitively) that there’s no need to change the Monarch’s status, citing past population plunges and recoveries. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a leading scientific authority on the status of species, recently downgraded Monarchs on their Red List of Threatened Species from Endangered to Vulnerable.

Some of the arguments are historical. Monarchs like milkweeds, and milkweeds like sunshine, and the treeless Great Plains is thought by some to be the historical center of both Monarch and milkweed populations. Too, there was lots of sunshine during the long postglacial period while trees moved back north after the most recent glacier pushed them south, and some speculate that milkweeds and Monarchs took that opportunity to push east and increase their numbers before the forests regrew.

The early settlers cut down swathes of America’s Great Eastern Forest to establish villages and farms, making the area sunnier and more Monarch/milkweed-friendly, and some say that Monarch populations are larger now than they were 200 years ago. Today, they say, Monarchs are adapting to modern stressors, and they’re establishing some non-migratory breeding communities in Florida and around the Gulf Coast. Monarchs, some scientists say, are not at risk, but the eastern Monarch migration may be (a distinction without a difference to Monarch lovers).

Did the Monarch’s eastward expansion into a glacially-modified landscape and later into a human-modified landscape artificially boost their numbers, so that what’s happening today is just a “course correction?” Should we base the butterfly’s status on the wintering numbers rather than the summertime population? On today’s numbers vs long-time averages? Is it better to err on the side of caution?” Will there, as Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch says “always be Monarchs?”

Only time –- and more research — will tell who’s got it right. In the meantime, what can we do to help?

- Plant native, not tropical, milkweeds for caterpillar host plants. The tropical milkweed Asclepias curassavica may discourage migration and encourage disease, and the toxins in its sap may be a bad match for Monarch caterpillars https://extension.umn.edu/

yard-and-garden-news/tropical- ;milkweed-bad-monarchs - Plant lots of native nectar flowers that will bloom throughout the summer for the butterflies;

- Reduce or discontinue pesticide use;

- The Xerces Society urges us to put our efforts into habitat improvement rather than into the captive rearing of caterpillars https://xerces.org/blog/keep-

monarchs-wild ; - Sign up for one of the citizen-based butterfly or caterpillar-monitoring programs https://monarchjointventure.

org/get-involved/study- .monarchs-community-science- opportunities

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/