by Kate Redmond

Bug o’the Week The 12 (or 13) Bugs of Christmas

Greetings of the Season, BugFans,

(13 bugs, because once she’s got her selection down to 13, the BugLady just can’t cut one more!)

A Cheery Thought for the Holidays, the average home contains between 32 and 211 species of arthropods (with the lower numbers at higher Latitudes and higher numbers as you head south past the Mason-Dixon Line). So, while the BugLady is celebrating The 12 (or 13) Bugs of Christmas, most BugFans could rustle up at least that many under their own roofs. Whether you see them or not, all kinds of invertebrates coexist with us daily, mostly staying under our radar until we surprise each other with a quick glimpse.

Here are a baker’s dozen of the bugs that the BugLady saw in 2023.

BALTIMORE CHECKERSPOT CATERPILLAR – According to one researcher, caterpillars are “essentially bags of macerated leaves.” What kind of leaves does a Baltimore Checkerspot caterpillar macerate? The eggs are laid in the second half of summer on, historically, White turtlehead, a native wildflower, and more recently, Lance-leaved plantain has been added as a host plant. Both plants contain chemicals that make the caterpillars distasteful to birds, though the turtlehead has higher concentrations of them. The butterflies have adapted to use an introduced plant, but the caterpillars don’t do as well on it (the BugLady has also seen them on goldenrod). Half-grown caterpillars overwinter, and when they emerge to finish eating/maturing in spring, the turtlehead isn’t up yet, so they eat the leaves of White ash and a few spring wildflowers.

LEAFCUTTER BEE ON PITCHER PLANT – Bumble bees and Honey bees are listed as the main pollinators of Purple pitcher plants, along with a flesh fly called the Pitcher plant fly (Fletcherimyia fletcheri), a pitcher plant specialist that contacts the pollen when it shelters in the flowers. But it looks like this Leafcutter bee is having a go at it.

SEVEN-SPOTTED LADYBUGS had a moment this year; for a while in early summer, they were the only ladybug/lady beetle that the BugLady saw. Like the Asian multicolored lady beetle, they were introduced from Eurasia on purpose in the ‘70’s to eat aphids. But (and the BugLady is getting tired of singing this chorus) they made themselves at home beyond the agricultural fields and set about out-competing our native species.

An Aside: Lots of people buy sacks of ladybugs to use as pest control in their gardens. The BugLady did a little poking around to see which species were being sold. Some sites readily named a native species, but most did not specify. Several sites warned that unless you are buying lab-grown beetles, your purchase is probably native beetles scooped up during hibernation, thus posing another threat to their numbers

SOLDIER FLY LARVA – The BugLady is familiar with Soldier fly larvae in the form of the flattened, spindle-shaped larvae https://bugguide.net/node/view/1800040/bgimage that float at the surface of still waters, breathing through a “tailpipe” and locomoting with languid undulations. So she was pretty surprised when she saw this one trucking handily across a rock in a quiet bay along the edge of the Milwaukee River. It appears to have been crawling through/living in the mud.

COMMON WOOD NYMPH – And an out-of-focus Common Wood Nymph at that. The BugLady has a long lens, and her arms weren’t quite long enough to get the butterfly far enough away to focus this shot. And it’s really hard to change lenses with a butterfly sitting on your finger.

FALSE MILKWEED BUG – Milkweed bugs are seed bugs that live on milkweeds, but if you’ve ever seen a milkweed bug that was not on a milkweed (usually on an ox-eye sunflower), it was probably a False milkweed bug. They’re so easily mistaken for a Small milkweed bug that one bugguide.net commentator said that all of their pictures of Small milkweed bugs should be reviewed. Here’s a Small milkweed bug with a single black heart on its back bracketed by an almost-complete orange “X” https://bugguide.net/node/view/2279630/bgimage; and here’s the False milkweed bug, whose markings look (to the BugLady) like an almost complete “X” surrounding two, nesting black hearts https://bugguide.net/node/view/35141. One thoughtful blogger pointed out that although it looks like a distasteful milkweed feeder, it’s not thought to be toxic. He wondered if this is a case of mimicry, or if the bug once fed on milkweed, developed protective (aposematic) coloration, and then changed its diet?

LARGE EMPTY OAK APPLE GALL – That’s really its name, but “empty” refers to the less-than-solid interior of the gall https://bugguide.net/node/view/54459 (which was made by this tiny gall wasp https://bugguide.net/node/view/260612). Galls are formed (generically) when a chemical introduced by the female bug that lays the egg, by the egg itself, and later by the larva, causes the plant to grow extra, sometimes bizarre, tissue at that spot. The gall maker lives in/eats the inside of the gall until it emerges as an adult. Some galls are made by mites – same principle.

SYRPHID FLIES are pretty hardy. Some species appear on the pussy willows and dandelions of early spring, and others nectar on the last dandelions of late fall. This one was photographed on November 17, on a sunny and breezy day with temperatures in the low 40’s, 12 feet off the ground, resting on the BugLady’s “go-bag” (the bag of extra clothes she carries up onto the hawk tower to deal with the wind chill).

WASP WITH SPIDER – The BugLady saw a little flurry of activity near an orbweaver web on her porch one day, but she got it backward. At first she thought that the spider had snagged the wasp (a Common blue mud dauber), but it was the wasp that hopped up onto the railing with its prey, part of the spider collection she will put together for an eventual larva.

SIX-SPOTTED TIGER BEETLES grace these collections perhaps more than any other insect, because – why ever not!

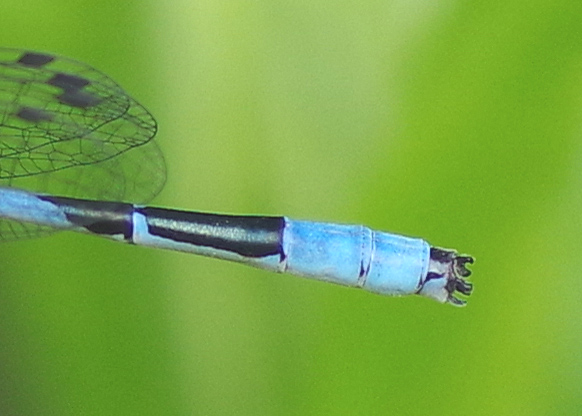

JUST-EMERGED DAMSELFLY – This damselfly was so recently emerged (possibly from the shed skin nearby) that its wings are still longer than its abdomen (basic survival theory says that you put a rush on developing the parts you might need most). Will a few of the aphids on the pondweed leaves be its first meal?

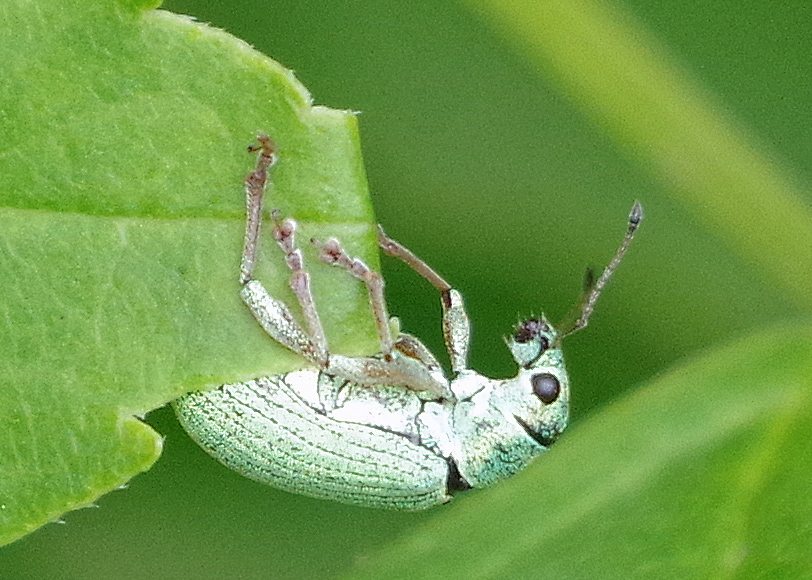

This is either a GREEN IMMIGRANT LEAF WEEVIL (Polydrosus formorus https://bugguide.net/node/view/1678834/bgimage) or the slightly smaller (and equally alien) PALE GREEN WEEVIL (Polydrosus impressifrons https://bugguide.net/node/view/1813505/bgimage). Whichever it is, it’s been in North America for a little more than a century. Bugguide.net calls them “adventive” – introduced but not well established. Eggs are laid in bark crevices or in the soil, and the larvae feed on roots. Adults eat young leaves, buds, and flowers of some hardwood, fruit, and landscape trees but are not considered big pests. Their lime-green color comes from iridescent, green scales.

And a DOT-TAILED WHITEFACE in a pear tree.

Have a Wonder-full New Year,

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/